Keeping an eagle eye on Drone Journalism

What journalists need to know about reporting with birds’ eyes

In short

Drones offer interesting perspectives for journalism. Drones equipped with cameras can take photos and videos from an aerial perspective, reaching inaccessible places or offering breathtaking footage. Still, journalists might hesitate to use drones for their work, because there are too many issues and unclear regulations.

This white paper will shed light on the disruptive impacts and implications of drone use on journalism as a business, as a practice and as an institution.

The paper starts with a short history of drone journalism, including the major kinds of drones available and their key features. Then, the key technical and business opportunities and challenges are outlined. Next, pro and contra arguments towards drone journalism will allow a better understanding of the controversy among media professionals, academics, lawmakers, authorities and the civil society. The main points are:

- Especially for geographic and war reporting, drones offer unprecedented access in combination with safety for a journalist’s body.

- Drones are relatively inexpensive gadgets inviting experimentation, but expert use requires training and experience.

- Citizens and policymakers remain skeptical towards drone use. Privacy violations, conflicts with authorities, or damages need to be kept in a drone journalist’s mind.

- The decision to invest in drone journalism should be guided by your editorial policy and the news themes your newsroom is prioritizing.

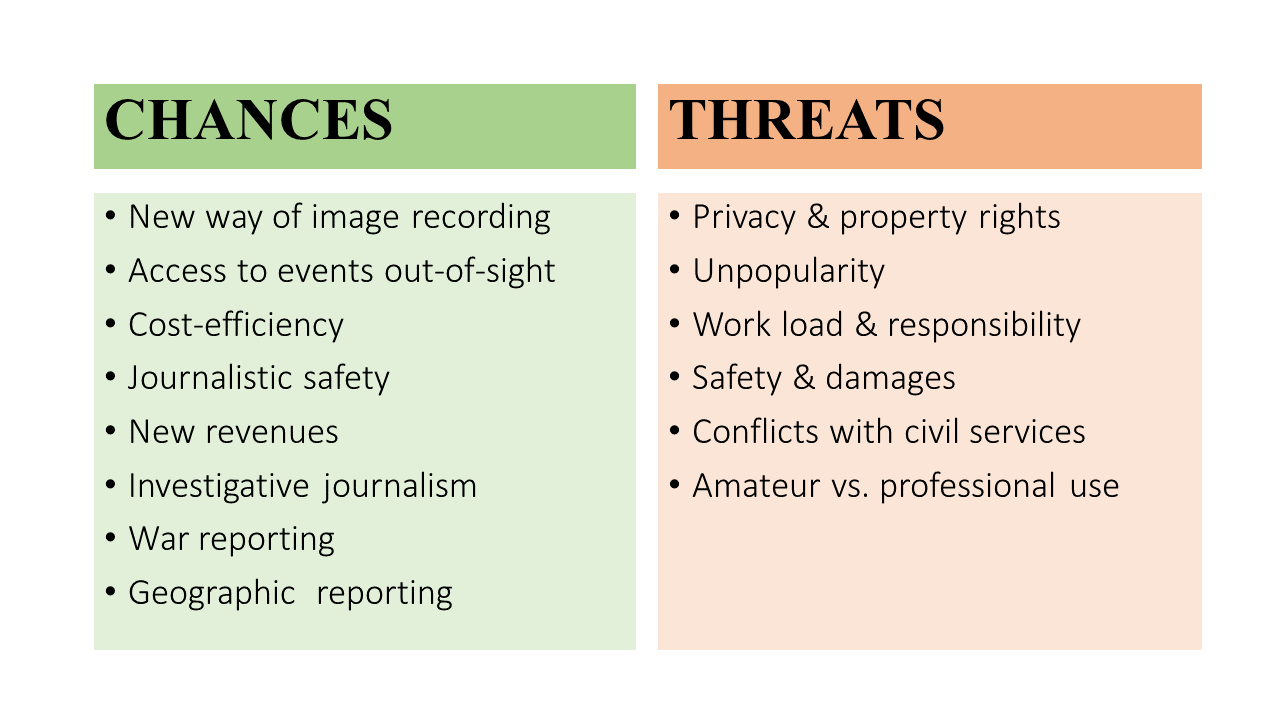

Next, we discuss the positive and negative outcomes of drone journalism. There is clearly a potential in the use of drones to cover situations that are dangerous or inaccessible for journalists, at a relatively low cost. On the other hand, there is no control on that access (e.g. no press card for drones) and a general drone use can foster surveillance culture.

We conclude that drone journalism will be a niche in the evolving news environment and outline different scenarios for different newsrooms, showing how:

- large media might choose to engage for cost-cutting reasons,

- average media should only invest when aligned with their editorial policy,

- freelancers could develop a successful specialty in drone journalism.

A birds’ eye on Drone Journalism

Drones are also known as “unmanned aerial systems (UAS)” or “remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS)”. Drones equipped with cameras can take photos and videos from an aerial perspective, that can be integrated into everyday news coverage. Reporters can either directly integrate the material into their online or TV news outlets, or they can indirectly make use of the materials as a source to feed their stories (especially in ethically critical cases).

It’s a bird… It’s a plane… It’s a drone

The first actor who used drones was the military that applied highly equipped aircraft for surveillance and attacks, e.g. the infamous RQ-9B “Predator”. However, commercial use of drones kicked off when software companies and engineers started constructing small, light-weight drones that were easy to control. At the same time, tiny but powerful cameras (like GoPro cameras) were produced and became cheaper. The major shift came when the industry discovered the commercial market of camera-equipped drones. Drone producers like Parrot or MikroKopter sell drones at affordable prices.

Since a couple of years, there are a lot more drone producing enterprises like DJI, Yuneec, Syma, Tekk, etc. competing on the commercial market. The market predictions from PricewaterhouseCoopers indicate tremendous future potentials of the commercial drone market: They prognosticate investments of 8.8 billion dollars until 2020 for the media and entertainment market.

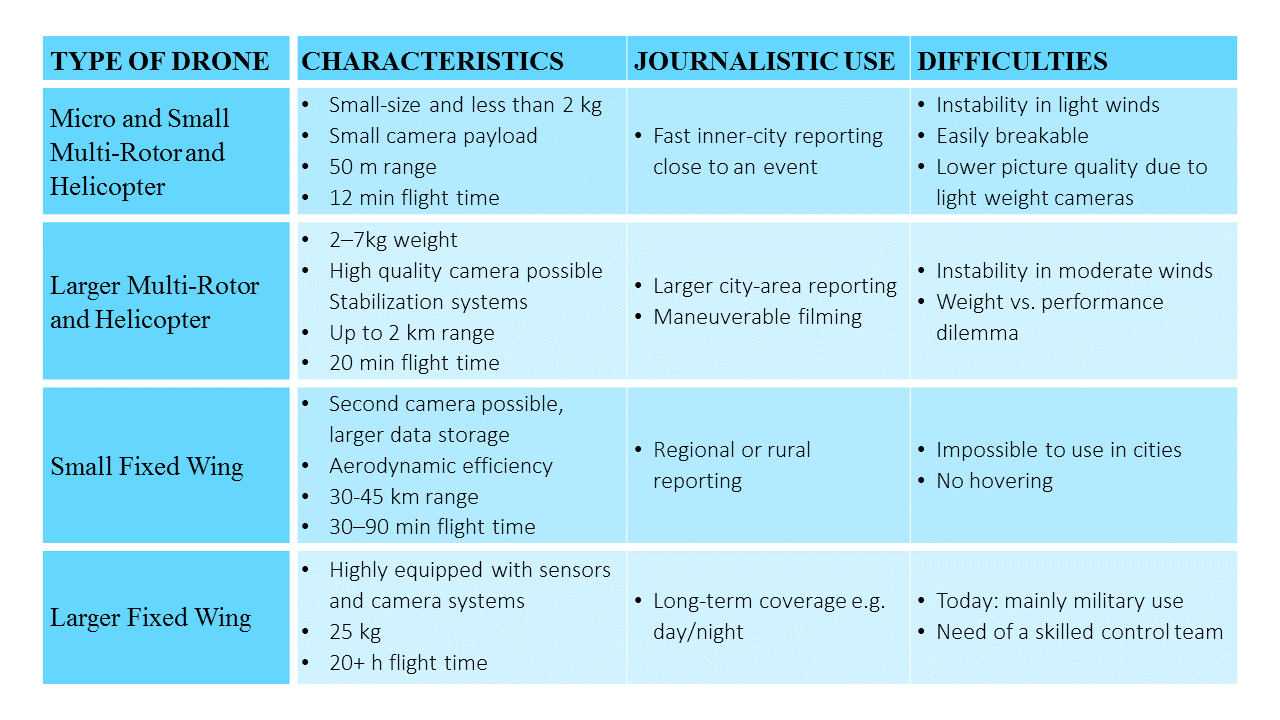

There exist several types of drones, each with different advantages and difficulties:

While the rotor drones are more applicable for immediate purposes such as protest coverage, the fixed-wing drones can be helpful in geographic reporting of natural disasters, nuclear accidental areas, or war zones.

A short history of Drone Journalism

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln established a Drone Journalism Lab in November 2011 aimed to make journalism more digital and innovative. In the lab, they build drone platforms for the use in the field. Their research focuses on ethical, legal and regulatory issues involved in using remotely piloted aircraft to do journalism. In the same year, the Professional Society of Drone Journalism was founded, an international organization dedicated to establishing a framework for the emerging field of drone journalism.

However in 2013, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) wrote a letter to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln drone program urging them to stop flying until the program obtains a Certificate of Authorization. After three years of waiting, the FAA published a new “small unmanned aircraft rule (part 107)” defining the circumstances allowing the use of drones for civil or commercial purposes. According to the Columbia Journalism Review, the new rules would simplify the incorporation of drone footage into everyday journalistic work. The event illustrates the regulatory tensions surrounding drone journalism.

Drone Regulations

Inthe European Union, the legal regulation of civil drone use is still in the works, even though national regulations exist. In Germany for example, drone regulation is the responsibility of the federal states. According to Süddeutsche Zeitung, the German Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure is working on a new regulation for civil drone use on a national level, which includes an obligatory license tag for drones weighing more than 250g as well as a license for the pilot.

In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) published the small unmanned aircraft rule in 2016: a commercial drone must be light-weight (less than 25 kg) and has to stay in visual line-of-sight of the pilot at all times. Drones may not operate over any persons not directly participating in the operation and not under a covered structure. Moreover, only daylight operations are allowed, and a drone must give the right of way to all other aircraft. Remote pilots require an airman certification with a small unmanned aerial systems rating by passing an FAA aeronautical knowledge test. For the registration, one has to be at least 16 years old.

“Under this regulatory framework, every newsroom will have drones and people certified to fly them. They’ll just be part of the equipment.” , says Matt Waite, founder of the Drone Journalism Lab at the University of Nebraska.

Drones are allowed to reach the maximum ground speed of 100 mph or 161 km/h, and a maximum altitude of 400 feet or 122 m above ground level. Pilots have to ensure the minimum weather visibility of 3 miles (4.8 km) from the control station. Before the flight, an inspection by the remote pilot in command is required.

Why journalists should care about Drone Journalism?

The functionalities of drones are potentially relevant for news professionals. They provide various advantages for news-gathering such as aerial reporting and access to places. Moreover, drones became smarter and more affordable over the last decade.

Drones make aerial reporting accessible to all

Drones offer unprecedented possibilities to journalists. One the one hand, drone journalism dramatically increases the frequency of aerial reporting. According to Rick Shaw of the Missouri Drone Journalism Program, for media companies that use a news helicopter, the change to drone journalism would be much more cost-efficient.

Before we had to hire a pilot, rent the airplane, and you were looking at $200 or $300 minimum for an hour to go up, and many times the pilots had a minimum of two or three hours. […] Now for that same cost, you can purchase a small unmanned aircraft, get someone on your staff trained, and use it repeatedly for a number of things. (reported by Columbia Journalism Review)

Once only wealthy media companies could afford a helicopter and a pilot for aerial reporting, now drones are cheap to buy and to operate and allow smaller media companies and freelancing journalists to cover aerial perspectives. Due to new technologies, the production of high definition or 3D images can be directly used for video news or live reporting, which makes media production more time-efficient.

On the other hand, by using drones, journalists can reach dangerous or otherwise inaccessible areas, providing information and fact-checks to the public.

In January 2015, both the Russian-backed rebels and the [sic] Ukraine claimed control over Donetsk Airport, which is battleground since the start of the conflict. At that moment, the fundraising collective for the Ukrainian army “Army SOS” posted a drone footage of the destroyed airport on Youtube. The video was spread by Vice and Mashable and went viral. From this footage, the Professional Society of Drone Journalists (PSDJ) mapped the area and compared the images to publicly available satellite images, creating a low-resolution 3D model of the airport. (reported by DutchNewsDesign.com)

Drone journalism offers a novel user experience

Drone journalism provides various business opportunities. Video content gathered by drones provides a novel consumer experience in terms of aesthetics, proximity, and oversight. This can either be used for extraordinary marketing campaigns via TV or social media channels, or it can be sold directly on news websites.

Still searching for online niches and profitable business models, media companies could create revenue in the niche of specialized drone journalism. For example in sports reporting, drone journalism offers totally new perspectives. In the future, this field might be covered by only a few players on the market — probably these will either be new start-ups, or big, global media companies.

“The newspaper was still for images but the Internet is for this”, says Lewis Whyld, a British photographer.

Furthermore, geographic coverage will become cheaper and more widespread, allowing also local news media on a tight budget to cover stories with large spatial applications, such as a forest fire or flooding.

“Lewis Whyld, a British journalist who has been building drones in his living room for years, went to the Philippines to capture the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan. In its deadly push through the country, the tropical cyclone had ripped houses and villages apart, burying people under rubble, and scattering large-scale detritus across the landscape. Using his drone, Whyld was able to fly over impassable roads and get to places others couldn’t. ‘I was finding dead bodies in areas the authorities couldn’t access,’ says Whyld, 36. ‘It’s not just about beautiful aerial shots. When covering the typhoon, it was accessing areas you couldn’t access on foot.’” (reported by The New York Times)

Albeit, before newsrooms can profit from drone journalism they need to invest in training and licensing their drone journalists.

Key challenges

Practical Implications

With the drones, several completely new journalistic profiles will enter the journalistic workplace. Depending on the type of the drone, these jobs will be done by one or more persons. In a newsroom, it also needs to be clarified who will be responsible for the drone specific tasks:

- Who decides which topics will be covered by a drone and which will not?

- Who is responsible for the functioning and maintenance of it?

- Who will be responsible in case of legal issues caused by drone use?

- Who edits the great amounts of photo or video material? …

However, in the precarious working environment journalists face right now, it needs to be considered that additional tasks for journalist will increase their workload even more. Facing legal issues like privacy and damages, drone use requires a high sense of responsibility from the remote pilot.

As mentioned above, drones provide the opportunity for self-employed journalists or freelancers to come up with an own start-up. Since there are small and inexpensive drones that can be handled by one person, they can easily create their own media website or sell their videos to major media companies in an entrepreneurial manner. However, becoming a drone journalist is coupled with time and money, which freelancing journalists should keep in mind when estimating their workload.

In 2011, the Polish drone producer RoboKopter flew one of their drones over the chaotic Independence Day protests in Warsaw. The confrontations among Polish nationalists, left-wing activists and the police have been recorded from aerial view. The drone created impressive cinema-like pictures in a spectacular aerial perspective. However, in the U.S. Occupy Wall Street protests, this would not have been feasible, since the police was closing the airspace over the event. Consequently, the recorded images from the Occupy protest had to be made in a traditional hand-held way. (reported by the blogger Robert Mackey)

Institutional Implications

Onthe one hand, the media function as a watchdog is reinforced since journalists can make use of a powerful new observation tool. Especially investigative journalism could evolve. Drones could be used to record illegal activities, environmental pollution on private land, black market activities, or unhygienic agricultural conditions.

On the other hand, there are various new possibilities for citizen journalism. Today, citizens report photos and videos taken with their smartphones on their social media channels. Tomorrow, they could share their drone recorded materials and participate in news coverage. However, ethical principles for the integration of drone footage need to be specified.

PRO & CONTRA DRONE JOURNALISM

Generally, it can be stated that media academics, journalists and media organizations are quite enthusiastic about drone use for journalistic purposes. In contrast, civil rights organizations, lawmakers, and the civil society remain rather skeptical about it and worry about privacy and physical injury.

Drone Enthusiasm

Journalists and news professionals tend to be enthusiastic about the possibilities of drone journalism. Already in 2011, the New York Times titled “Drone Journalism arrives”. In 2012, the Knight Foundation spend a 50,000 $ grant to Matt Waite, who founded the Drone Journalism Lab. The goal was to do research and experimentation into the use of drone vehicles as news and information-gathering tools, to study the ethics of these techniques and to publish case studies and best-practices guides.

In 2014, Journalism.co.uk predicted robots and video capture drones to be technology trends that “journalists should watch”. In 2015, ten news media companies have partnered with Virginia Tech for the testing of small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to gather news. Virginia Tech would have seen this collaboration as a key to fundamental research to use UAS for the news and broadcasting industry on a routine basis.

Browsing through the internet, you will find many extraordinary photos and videos taken by drones. The Time Magazine, for example, was just recently celebrating the “new perspective on the world” in an article which contained the best drone shots from 2016.

In December 2016, Chinese English-language newspaper China Daily signed a contract with a domestic drone producerto enrich their digital news coverage on a routine basis.

According to the Drone Journalism Lab, drones would be the ideal platform for journalism for two reasons:

- “a growing appetite for unique online video in an environment of decreased budgets” and

- “restricted or obstructed access to stories”.

Drone fear

But not all media professionals are enthusiastic towards the emerging drone use in journalism. The editor John A. Moore elaborated his doubts towards daily drone use in journalism. According to him, one of the central questions would be how many news media drones should be allowed by the authorities to cover an event. A limitation of several or dozens would be hard to implement since drones could not easily present their press pass like journalists would do. But without a press pass, it would be impossible to distinguish amateur drone pilots from drone journalists.

Steve Coll, who is the dean of the Journalism School at Columbia University, has frequently written about the technology and its military applications. For him, drones are objects that would capture people’s anxieties and imagination. He stresses in an interview with the Columbia Journalism Review, that before using a flying camera, journalists should ask themselves: “What can you use a drone for, that you can’t achieve by other means, that really matters, that is in the public interest, and is not just for the sake of doing it?”

But just because you can use a drone, doesn’t mean you should use a drone.

Furthermore, there are several legal issues. Privacy issues will occur when people who expected to be private (e.g. on a balcony) are filmed by a press drone. Google has responded to a similar problem with their maps service by blurring people’s faces. Yet, it remains unclear how such a method could be implemented in video data in a daily news routine. Violations of privacy and property rights will cause both ethical and legal implications.

Additionally, the Rutherford Institute, which is dedicated to the defense of civil liberties and human rights, warns the threats to Americans’ safety and privacy posed by the domestic use of drones. Equally, lawmakers worry about privacy rights. In a letter to the Federal Aviation Administration, two senior lawmakers wrote that drones would be powerful surveillance instrumentswithout adequate privacy protections.

Moreover, drones are not very popular among citizens. According to a representative Associated Press-GfK poll among the American citizens from 2014, almost half of the respondents (43 %) say they “strongly oppose” or “somewhat oppose” the commercial use of drones. Whereas 35 % neither favor nor oppose, and only 21 % of the respondents favor commercial drone use. Three quarters state to be moderately to extremely concerned about the danger that drones pose towards aircraft and towards people on the ground. 86 % of the respondents stated to be concerned with privacy.

The drone journalism professor Matt Waite discusses these ethical question with his students. According to the Columbia Journalism Review, he claims that journalists have to start thinking about the impact of drones: are they harassing or distracting? Do they cause panic? Are drone journalists harming people psychologically or needlessly invading their privacy?

Regarding the above-mentioned new FAA rule, the Poynter Institute remains skeptical. They do not see how the legal certificate would be sufficient to handle drones professionally and worry about a few experienced remote pilots doing journalism.

Finding a reasonable solution

According to the Reuters Institute Report on RPAS, journalistic drone use would certainly create conflicts with law enforcement and emergency services. But they add that this kind of conflicts would have previously existed for media helicopters and live broadcasts. Moreover, they warn for too much optimism related to drones in war zones. The drone’s radio signal could be tracked and the journalist could be targeted and harmed.

Thomas Hannen from the BBC sees the advantages of drones but concludes that the BBC does not “see them as a replacement for a news helicopter” — as the Guardian reported.

Final notes: being ready for take-off

All journalists and media professionals should keep in mind the skepticism of the population and lawmakers towards drone use. Especially regarding their audiences, journalists have to consider carefully if the new way of reporting and overcoming barriers equals a possible loss of journalistic credibility caused by privacy violations, conflicts with authorities, or damages.

However, you can benefit from a bird’s view on the world which allows increased access, potential new revenues and markets, unprecedented geographic and war reporting and safety for a journalist’s body. Another key point is that, in exchange for all the advantages they provide, drones are relatively inexpensive gadgets.

For media organizations, it is a rather strategic decision whether to invest in drone journalism or not. Large media corporations that already use a news helicopter should definitely take a look on the resources they can save if they invest in drones. Important in that case is to take into account the amount of training their journalists need before being professional drone journalists.

Average or small media companies should only invest in drone journalism if it benefits their journalist working on investigative, war, sports, and geographic reporting. If your team rarely works in these fields, it might be better not to invest in drone journalism, unless, they want to broaden their coverage into these fields.

Freelancers who decide to go for drone journalism could succeed as a highly specialized media worker with their own enterprise in an emerging business. But in a precarious working environment, they should consider being exploited by major media. As a consequence, their situation could worsen, since self-employed journalists carry the financial risks of the purchase and training alone.

As described above, drone journalism will be a niche in the evolving news environment. Drone recorded materials will probably be bought and sold a lot since economically, it is more cost-efficient for small and average media companies. Probably, they will rather buy professional drone shots and videos than invest in their own drone journalist. As a start-up or as a big player the in media business, however, investing in drone journalism to fill this niche might be fruitful. After all, when it comes to drone journalism, the sky is the limit.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Bal, H. M., & Baruh, L. (2015). Citizen Involvement In Emergency Reporting: A Study On Witnessing And Citizen Journalism. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture, 6(2), 213–231.

Cohen, N. S. (2015). Entrepreneurial Journalism and the Precarious State of Media Work. South Atlantic Quarterly, 114(3), 513–533.

Cook, C., & Sirkkunen, E. (2013). What’s in a Niche? Exploring The Business Model of Online Journalism. Journal of Media Business Studies, 10(4), 63–82.

Moore, J. A. (2014). Robot vs. Human. Columbia Journalism Review, 53(2), 6.

Picard, R. G. (2014). Twilight or New Dawn of Journalism? Digital Journalism, 2(3), 273–283.

No comments:

Post a Comment