Obituary: Jin Yong fused martial arts fantasy, history and romance into must-read novels

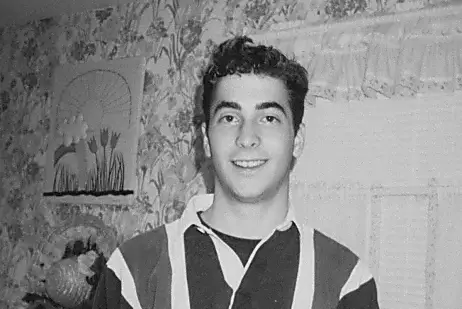

Louis Cha, the newsman and master storyteller whose unputdownable wuxia novels made him the most popular living Chinese author in his lifetime, has died in Hong Kong at the age of 94.

He died in Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital on Tuesday afternoon (Oct 30), said Ming Pao Daily News. No cause of death was given. In April, The New Yorker magazine said he had "been frail since suffering a stroke in 1997". During an interview with the magazine in 2014, "he is unable to walk or write, and speaks with difficulty, relying on a retinue", The New Yorker added.

Cha was known to millions by his pen name Jin Yong.

Starting with The Book And The Sword in 1955 and continuing until the final instalment of The Deer And The Cauldron in 1972, Cha was a phenomenon, fusing martial arts fantasy, history, political allegory, heartfelt romance and urgent prose into must-read newspaper serials.

His 15 wuxia titles were serialised in publications including Hong Kong's New Evening Post and Ming Pao (which he founded in 1959, after the success of his third novel, Legend Of The Condor Heroes) and Singapore's Nanyang Siang Pau and Shin Min Daily News (which he established in 1967 and which had first dibs on his latest novel then, The Legendary Swordsman).

The works have spread across Asia as books, radio serials, movies, ubiquitous television dramas and video games. The books have been translated into Vietnamese, Japanese and English, among other languages, and have had sales estimated as high as 300 million - or more than one billion, counting bootleg copies.

The most successful of Cha's multiple-volume novels, including Legend Of The Condor Heroes, Return Of The Condor Heroes, Heaven Sword And Dragon Sabre, Demi-Gods And Semi-Devils, The Legendary Swordsman and The Deer And The Cauldron, have long entered the canon of popular culture in the Chinese-speaking world.

In Singapore, for example, a couch potato who has never read a word of Cha's may know his most beloved characters - Guo Jing, the slow, steady hero who grows up on the Mongolian steppes; the rebellious Yang Guo, who falls in love with his mentor Xiaolongnu; Zhang Wuji, the gentle, indecisive genius who takes charge of the Ming Cult - from the various TV adaptations.

A couple of generations ago, a Rediffusion listener in the 1960s might have been acquainted with Cha's tales, as retold by Hokkien storyteller Ong Toh.

And if the couch potato and the Rediffusion listener had caught the 2004 Stephen Chow comedy Kung Fu Hustle, they would have got the joke when the drunk Landlord (Yuen Wah) and the chain-smoking Landlady (Yuen Qiu) are revealed to be Yang Guo and Xiaolongnu, the once glorious couple who have gone to seed after retiring from the pugilistic world.

The wuxia genre arguably dates back to China's Han dynasty, when historian Sima Qian (145BC to 87BC) gave a chapter to Confucian knights errant in his seminal Historical Records.

In 1954, the form was revitalised when the New Evening Post seized on the Hong Kong public's mania for a duel between martial artists Chen Kefu and Wu Gongyi in Macau and quickly serialised a Liang Yusheng wuxia novel, Dragon And Tiger Vie In The Capital.

Liang is the pseudonym of Chen Wentong, Cha's colleague and friend at the Post, which was the evening edition of Ta Kung Pao. Both Chen and Cha were descended from Chinese scholars and had resettled in Hong Kong, around the time the communists took over the Chinese mainland in 1949.

In 1955, Cha followed Chen with his maiden wuxia novel, The Book And The Sword, for the New Evening Post.

Cha would dominate the genre with his brand of wuxia fiction, which was infused with his concern about a China in the throes of Maoism and steeped in the history, culture and philosophy of the homeland he had left. In his most prolific years at Ming Pao, he was said to be writing editorials with his right hand and daily instalments of wuxia serials with his left.

After communist leader Mao Zedong unleashed the Cultural Revolution in the mainland in the late 1960s, Cha not just editorialised against it from Hong Kong but also wrote allegories of power-hungry pugilists and cultish hysteria into his serials. Leftist extremists in Hong Kong responded by putting Cha on their assassination list. When leftist riots erupted there in 1967, he retreated to Singapore for one and a half months.

His books were still banned in China in 1981, when his request for a meeting with Mao's reformist successor, Deng Xiaoping, was granted.

Cha had defended Deng in Ming Pao when the moderate revolutionary was banished to Jiangxi province during the Cultural Revolution. And Deng turned out to be a fan of the author. After returning from the political wilderness in the early 1970s, he was said to have asked for a set of Cha's books to be bought for him from outside the Bamboo Curtain.

At the meeting in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, to which Cha was accompanied by his family, Deng said in greeting: "We're already old friends, I've read your novels."

In 1984, China lifted the ban on Cha's books, effectively allowing millions of mainland Chinese to catch up with the rest of the Chinese-speaking world. Passages from the page-turners, which were once deemed unworthy of serious attention, have also been printed in textbooks in China and Singapore.

Cha was born on March 10, 1924, into an illustrious scholarly family in the town of Yuanhua in Haining county, Zhejiang province, China. His pen name, Jin Yong, came from the last character of his name, Zha Liangyong. (In Chinese, the two yongs are written differently.)

Five ancestors, all elite Hanlin scholars, had served under the Qing emperors Kangxi and Yongzheng. Cha - a direct descendant of one of them, calligrapher Zha Sheng - was brought up in a house of which one section bore a plaque bestowed by Kangxi.

His grandfather Zha Wenqing had been a magistrate during the Guangxu reign. His father Zha Shuqing had received a Western education and his mother Xu Lu was a daughter of a business family; poet Xu Zhimo was her distant nephew.

Young Liangyong, the second of the couple's seven children, was a bookworm, devouring the Ba Jin novels his big brother bought from Shanghai, and other books borrowed from cousins and uncles.

In a rare autobiographical story, Yueyun, Cha wrote about his privileged childhood against a backdrop of social injustice in pre-communist China. Yueyun is the name of his child servant, a girl put up as collateral for a loan her parents got from his parents.

"His father and mother didn't do bad things themselves nor oppressed others," Cha wrote. "However, they acted unconsciously in accordance with the system and methods passed down by their ancestors, living comfortably themselves and being indifferent to others' hunger and suffering."

In 1939, Cha was 15 when he published his first book, a junior high school entrance exam guide that he compiled with two friends. It was a bestseller, earning enough money to last the trio until they went to university in Chongqing. In 1941, a head instructor expelled Cha from school for posting a wall newspaper with satirical content, but the principal helped transfer him to another school.

Despite the early promise he showed for publishing, Cha hoped to be a diplomat and enrolled at the Central School of Governance in Chongqing in 1944. But he was forced out of school after complaining about the behaviour of student members of the governing Kuomintang. In 1948, he finally graduated with a degree in international law from Soochow University in Shanghai.

But in the interim, he had fallen into journalism, working as a reporter for the Southeastern Daily in Hangzhou in 1946, and moving to Ta Kung Pao in Shanghai as a translator of international news in 1947. By 1948, he had been transferred to the Hong Kong branch of Ta Kung Pao.

After the communists swept into power in 1949, his father was deemed an oppressive landowner and executed. Following the news of the death, Cha "wept for three days and three nights in Hong Kong, and was sad for half a year, but he didn't hate the army that killed his father", he wrote in Yueyun. "Because thousands, tens of thousands, of landowners had been killed in all of China; this was a big upheaval."

Consequently, because "he always felt the weak should not be oppressed", he began writing wuxia novels, he said.

In his novels, he incorporated the personal and the political, stories from his childhood and larger topics.

The Book And The Sword was woven out of a legend in his hometown that the Qianlong Emperor was not a Manchu but a Han Chinese who had been switched at birth. A Deadly Secret, about a young swordsman framed for murder, was inspired by the true story of a Zha family employee whom Cha's magistrate grandfather had smuggled out of prison.

And spanning the novels is Cha's great theme, Chinese identity. Many of them take place in fractious periods in Chinese history, when China was at risk from or ruled by the nomadic Khitan tribes, the Mongols, the Manchus and other non-Han Chinese ethnicities.

In The Deer And The Cauldron, protagonist Wei Xiaobao is a prostitute's son of unknown paternity - he may or may not be fully Han Chinese - a rascal redeemed by his loyalty to his friends. Although illiterate, he has been profoundly influenced by the tales of Three Kingdoms-era heroism he heard from storytellers. And Cha suggests it is the stories, mere sips from the fountain of Chinese culture, that have kept Wei honest.

Cha married thrice. His first wife was actor Du Zhiqiu's sister, Du Zhifen. They married in Shanghai in 1948 and she moved to Hong Kong with him, said Ta Kung Pao. They divorced in the 1950s.

His second wife was journalist Zhu Mei, with whom he had two sons and two daughters. Their marriage was deteriorating around 1976, the year their 19-year-old son, a freshman at a university in the United States, committed suicide. Cha later said: "My marriage might have affected him, I let him down."

Near the end of his second marriage, Cha befriended waitress Lin Leyi, about three decades his junior, in a restaurant near the Ming Pao office that he frequented, said Ta Kung Pao. They married in the 1970s.

He did not write another novel after The Deer And The Cauldron in 1972. Instead, he made two rounds of revisions to all the wuxia serials, a project that would conclude with the re-release of The Deer And The Cauldron in 2006.

"Jin Yong's novels are not well-written," he wrote in Yueyun.

But "when he was writing and later rereading his own works, he often shed tears over his characters' misfortunes. When he wrote that Yang Guo waited in vain for Xiaolongnu till the sunset, he sobbed. When he wrote that Zhang Wuji and Xiaozhao were forced to break up, he wept. Writing that Xiao Feng killed his beloved Azhu because of a misunderstanding, he wept even more sadly".

The stories were from his heart, and they have reached countless other hearts.

No comments:

Post a Comment